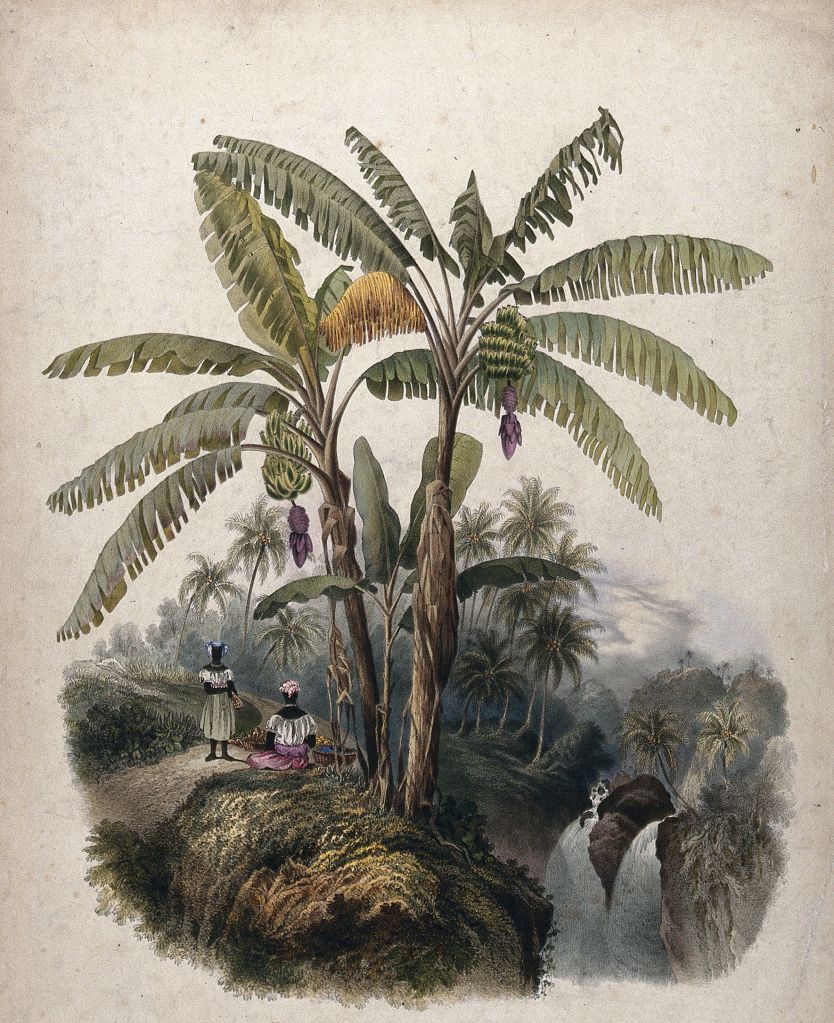

Image credit: Plantain trees (Musa x paradisiaca) growing by a waterfall with two women resting beneath them. Coloured lithograph by J.B.Kidd, c.1840 (Wellcome Collection)

‘Sacred Black Ecologies,’ (a concept I coined), is a transoceanic framework, drawing on community co-production and artistic and scholarly collaboration which positions land, water, and plant life as living archives, temporal epistemologies and geographies.

Jamaica serves as the project’s initial site of enquiry, operating allegorically to hyper-local diasporic communities in the United Kingdom, Anglophone Caribbean and West Africa, tracing the transatlantic routes of displacement, extraction, and resistance. Sacred Black Ecologies builds upon some of my earlier works such as: ‘Ecologies of Care’ (2020), Ecologies of Care 2.0 (2021), Black Futurism in Times of Climate Crisis (2022), Black Queer Ecologies (2022), Let the Emerald Village Carry Me (2022) 198 Contemporary Arts & Learning; Autograph.

Sacred Black Ecologies also emerges from my engagement with the Hans Sloane herbarium at the Natural History Museum. Sloane’s collection, much of it gathered during his 1687–1689 voyage to Jamaica, contains hundreds of specimens of flora and fauna removed from the island during the height of the plantation economy. These plants were catalogued as imperial assets, their indigenous uses often stripped of cultural context and re-inscribed into European scientific taxonomies. The herbarium is not a neutral archive: it is a material record of ecological dispossession and extraction, revealing how colonial science operated as an extension of the plantation system.

Yet these plants are not inert; their genealogies persist in the landscapes and practices of the Caribbean and African diaspora. By tracing these lineages, Sacred Black Ecologies repositions the herbarium as both evidence of colonial harm and a catalyst for decolonial recovery, a methodology that is grounded in ancestral memory, indigenous cosmology, and contemporary struggles for climate and land justice. Through curatorial, archival, and spatial practices, the project interrogates how land, ecology, and climate justice are negotiated across these interconnected geographies, foregrounding the legacies of colonial extraction and their contemporary resonances.

Sacred Black Ecologies in Jamaica revisited some of these same plants in their living contexts. At Castleton Gardens, itself a site shaped by botanical imperialism, we encountered species present in Sloane’s herbarium. Here, the contradiction was stark: landscapes cultivated through colonial exploitation now serve as spaces of leisure and healing. This tension reflects the broader postcolonial condition, the necessity of holding rupture and remedy together, of recognising land as both wounded and resistant. Our visit also extended to Norsehill Botanical Gardens, where we met Mr. Valentine, a landworker in his seventies whose deep knowledge of plants, cosmology, and African indigenous spirituality illuminated the ways land is cultivated not only for food or beauty, but for ritual and relational care. His understanding of how to create a “friendly environment” for both plants and people underscored the interdependence of ecological stewardship and cultural continuity.

Climate change deepens these entanglements. Rising seas erode coastlines, saltwater infiltrates crops, and seasonal patterns destabilise. Yet, amidst these disruptions, ecological continuity persists through practices such as boiling lemongrass for tea or drying guava leaves for healing. These acts represent a living counter-archive to the Sloane collection, a knowledge system that is not frozen in herbarium sheets but carried in bodies, kitchens, and communities.

Decolonisation, in this context, is less about simply recovering what colonial archives hold and more about reanimating what they could never contain: embodied, migrational, and ancestral knowledges. Beginning in Jamaica but extending to the wider Caribbean and West Africa, Sacred Black Ecologies situates these practices within the long temporal and spatial arcs of the transatlantic world.

By returning to the sites and species of Sloane’s collection, Sacred Black Ecologies bridges past and present, archive and field, Britain, the Caribbean, and West Africa. Sacred Black Ecologies redefines climate justice as inseparable from memory work, spirituality, indigenous knowledge insisting that the reparations we imagine for climate and land must also account for the deep temporalities of displacement, survival, and care.

This is beautiful beyond words. Thanks so much for sharing.

Katie Numi Usher Art has, and continues, to write me into capital H history which is intent on Black women erasure Patreon https://www.patreon.com/c/katienumi833 Youtube https://www.youtube.com/katienumiusher

LikeLike

Truly beautiful in every way.

LikeLike

A great read. Sacred Black Ecologies is important, insightful and essential work that you’re creating. I was *snaps fingers* to this whole piece but especially to “a knowledge system that is not frozen in herbarium sheets but carried in bodies, kitchens, and communities”. Period!

LikeLike